Drugs and Conspiracy Theories

Conspiracy theories are the simple, comforting stories we tell ourselves to understand awkward, complex problems. Narcotics trafficking has been generating such theories for over a century. This should come as little surprise. The underworld offers particularly fertile soil in which these narratives can flourish. Since drug prohibition this world has been closed and secretive. As a shifting, multilayered market ecosystem, it eludes clear explanation. And drugs, as substances which affect our blood and our behavior, provide rich metaphorical material for understanding more general changes in our societies and our nations.

Somewhat inevitably, the loudest drug conspiracies have mapped over the most popular prejudices. In the United States, for example, observers have avoided uncomfortable questions about doctors, drug companies, medical care, inequality, and the deleterious effects of overwork, lack of work, and war. Instead, they have blamed drug use on a shuffled deck of outgroups including (but not limited to) Chinese, Mexicans, and African Americans.

Stories of secretive Chinese gangs and cartoons of dissolute Chinese men smoking opium were part of the first U.S. opium panic in the 1870s and 1880s.

Yet not all conspiracy theories emerge at the center. And over the past century, many of these outgroups have developed their own simple narcotics narratives. These flip the blame for drug use back onto the prohibitionists, back onto the U.S. state. They are counter-hegemonic conspiracy theories; tall tales from the periphery. Perhaps the most notorious recounts how the CIA flooded U.S. cities with crack cocaine to pay for the Contra counterinsurgency in Nicaragua.

Perhaps the most famous drug “conspiracy theory” claims that the CIA “caused” the U.S. crack epidemic.

As historians, we tend to shy away from conspiracy theories. We tend to file them away in a box marked “mad” together with tales about aliens, pyramids, Jews, lizards, and banks. Often there is good reason. Many of the most dominant theories lack any evidence and are based solely on an unholy blend of ignorance and prejudice. (African Americans, for example, are still to this day connected to the rise in crack cocaine use; yet crack use among African Americans was always less per capita than among white Americans). They often intersect with moral panics. And they are useful – only – for mapping out the peaks and troughs of ignorance and prejudice.

Doing history in reverse

However, other conspiracies involve rather different dynamics. To survive in the competitive marketplace of popular rumor, without the backing of the mass media, counter-hegemonic conspiracy theories – in particular - need a smattering of facts. Without them, they sink and fade. As historians, we often dismiss these facts, grouping them together with the wild tales that they undergird. It is easy to do so. The facts often lie beyond the reach of archive-bound historians; and the tales based on them are often so unhinged they repel rational analysis.

Yet faced with one of these conspiracy theories, there is still a job for the historian. We can place these theories in their broader cultural contexts – map out the fears and vulnerabilities that make these theories stick. And we can also pick through these theories, tease out the blend of facts and misunderstandings, and suggest how these theories emerged. Such an approach often seems to run contrary to traditional historical method. It involves deconstructing rather than building a narrative. And it involves sifting rather than amassing vast quantities of evidence. It can seem, in short, like doing history in reverse.

The U.S.-Mexican Morphine Pact

This short essay is my first attempt to do this, to trace the origins of one of Mexico’s most pervasive drug conspiracy theories. It is inspired, in part, by Gabriel Gatehouse’s wonderfully thoughtful and balanced examination of the roots and the trajectory of QAnon. But it is also a response to writer, David Dorado Romo’s, provocative musings on the border, conspiracies, and World War II.

Traffickers have smuggled opiates through Mexico and into the United States since the Harrison Act of 1914. At first, some of the opium came directly from China, into Mexico’s Pacific ports, and over the border at Baja California. The rest came pre-processed from Europe as morphine and heroin, entered at the Gulf ports of Veracruz and Tampico, and was then transported to the border by train. But by the 1930s Chinese and Mexican peasants were also growing opium poppies. And within a few years entrepreneurial local chemists were transforming the sticky black gum into heroin and morphine. By the early 1940s homegrown Mexican opiates were hitting the U.S. market.

Yet in the Golden Triangle, the heartland of Mexico’s drug trade, locals have always told themselves another story. They claim that the country became a major producer of opium poppies on U.S. orders. According to this tale, during World War II U.S. agents signed a secret pact with the Mexican authorities to grow poppies and produce morphine for wounded U.S. soldiers.

The most influential telling is courtesy of the Sinaloa intellectual and playwright, Antonio Haas. According to his 1988 article “Drugs and Hypocrisy (Letter to the Ambassador)”

“the first to encourage the sowing of poppies in Mexico was the government of F.D. Roosevelt during the years of the Second World War. The aims were humanitarian because the production of the Turkish monopoly was in the hands of the Axis and the allies needed morphine for their injured soldiers. President Avila Camacho agreed to the project, which was carried out in semi-secret in the Sierra of Sinaloa with peasants from the surrounding area and the armies of both nations keeping watch”.

Haas even offered evidence for his plot. He claimed that during the war he had rented his house out to the U.S. consul in Mazatlán and overheard the official concocting the plan.

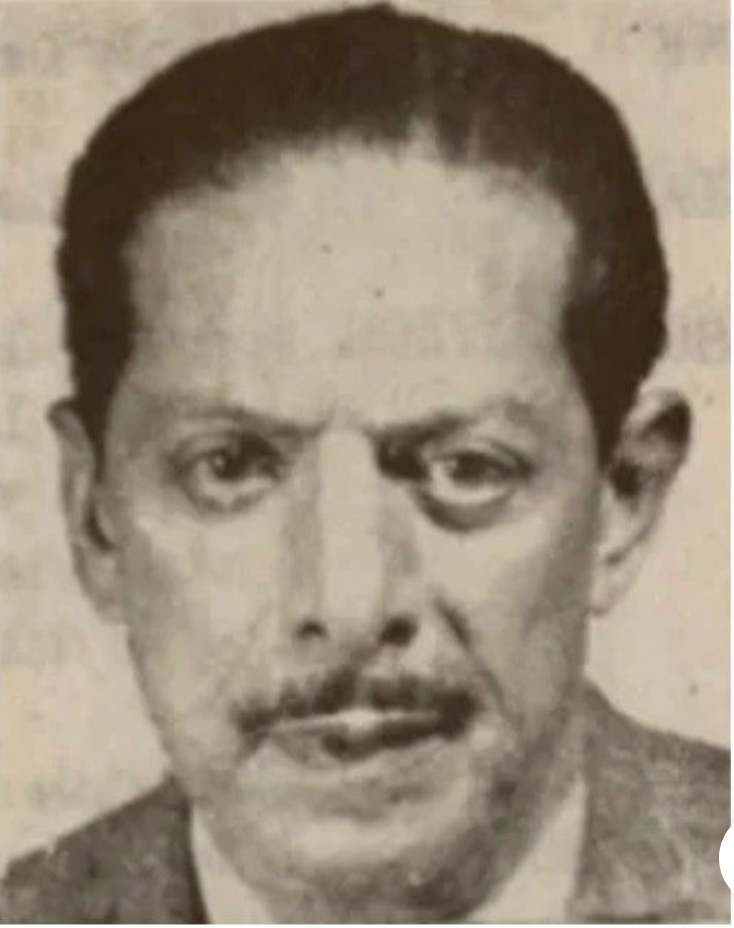

Antonio Haas, the Mazatlán dramatist and cultural entrepreneur. He was the first writer to voice some evidence of a U.S. plan to sign an unofficial morphine production pact with Mexico.

Over the passing decades the story has taken root. Evidence has been added; memories have shifted; fiction and non-fiction have intertwined. In 2005 the Sinaloa author, Leónides Alfaro Bedolla published Tierra Blanca, his gripping novel about the early years of the trade. The book repeated Haas’s claim that it was a secret treaty between the U.S. and Mexico which first brought opium poppies to the mountains of northwestern Mexico. Two years later, journalists tracked down the son of one of the Chinese farmers charged with introducing poppy farming into the Sinaloa mountains. Alonso Amarillas recounted how his father, José, was the first man “that brought the seed, sowed, and processed opium gum because of the treaty between Mexico and the United States. He taught many to work it. And we made good money in those years. That is what we used to do those of us who lived in the Sierra”. And in the same year another Sinaloa journalist, Judith Valenzuela Ortiz, published an article, which provided an overview of the theory and quoted Tierra Blanca as its historical source.

José Leónides Alfaro Bedolla with Tierra Blanca his novel based on the memories of many former traffickers.

The timing of such retellings is instructive. Difficult times call for simple stories. In 1988, in the wake of the murder of DEA agent, Enrique “Kiki” Camarena, the DEA’s Operation Leyenda was in full swing. U.S. drug officials were busy infiltrating Mexican drug networks, and kidnapping, and killing Mexican drug traffickers. Sinaloa was a bloodbath. Between 2005 and 2007 conflicts between criminal networks and between criminal networks and the police were causing a similar upswing in murders. What better way to explain away the power of drug traffickers than locating the origin in the secret machinations of the United States?

How a conspiracy theory comes about

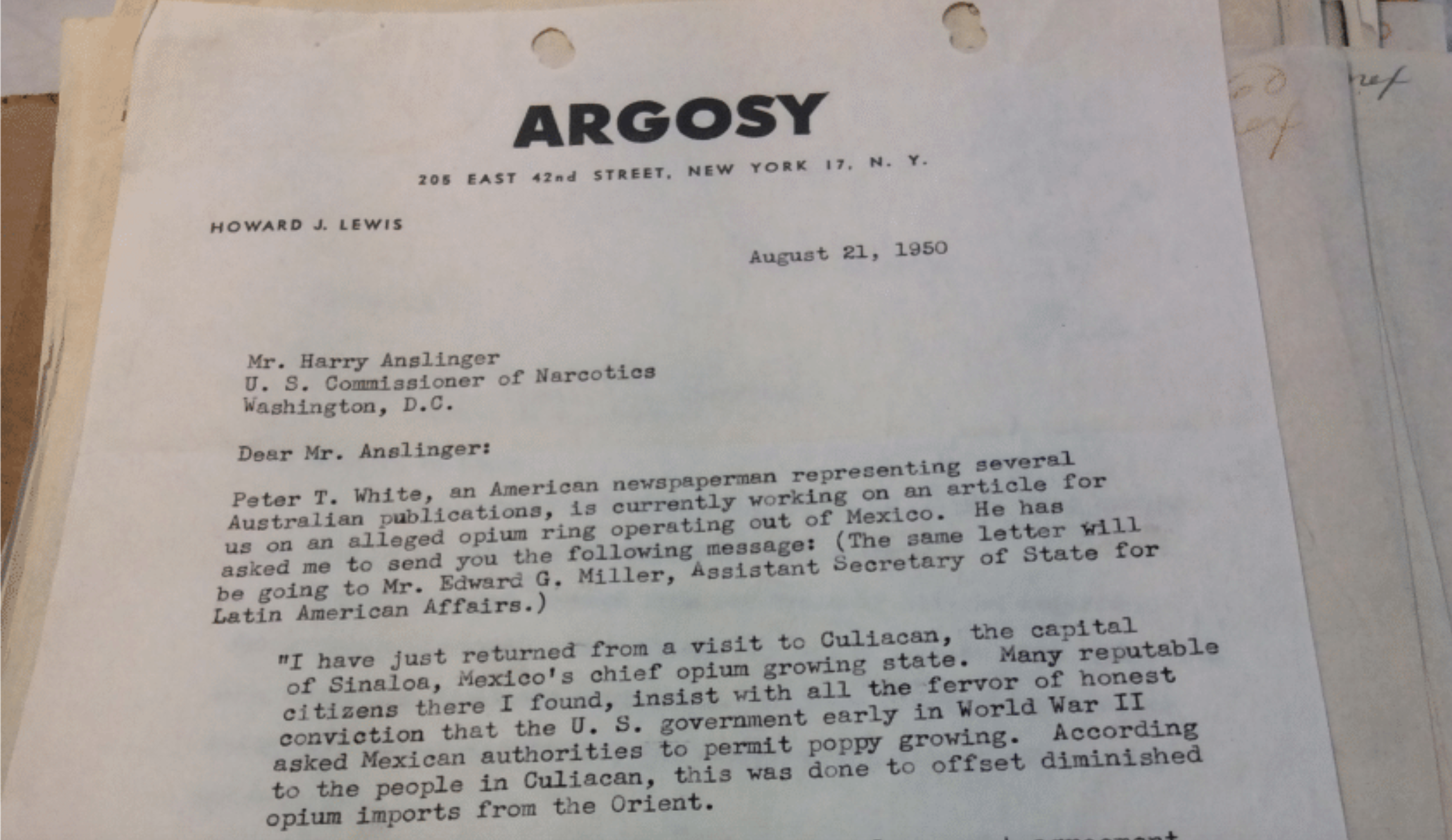

Though Mexico’s literati have only recently picked up on the U.S.-Mexican morphine pact, in Sinaloa the tale goes back decades. As early as 1950, a U.S. journalist reported to Harry Anslinger (head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics) that he had just come back from a fact-finding mission in the Sinaloa capital of Culiacán. It was another tense time, and the place was just recovering from Mexico’s first militarized counter-narcotics campaign.

“Many reputable citizens there… insist with all the fervor of honest conviction that the U.S. government early in World War II asked Mexican authorities to permit poppy growing…. This was done to offset diminished opium imports from the Orient. On VJ day the United States broke the agreement and sent swarms of agents into Sinaloa to break up the opium gangs”.

The first mention of the supposed U.S.-Mexican morphine pact, NARA, RG170, Box 23

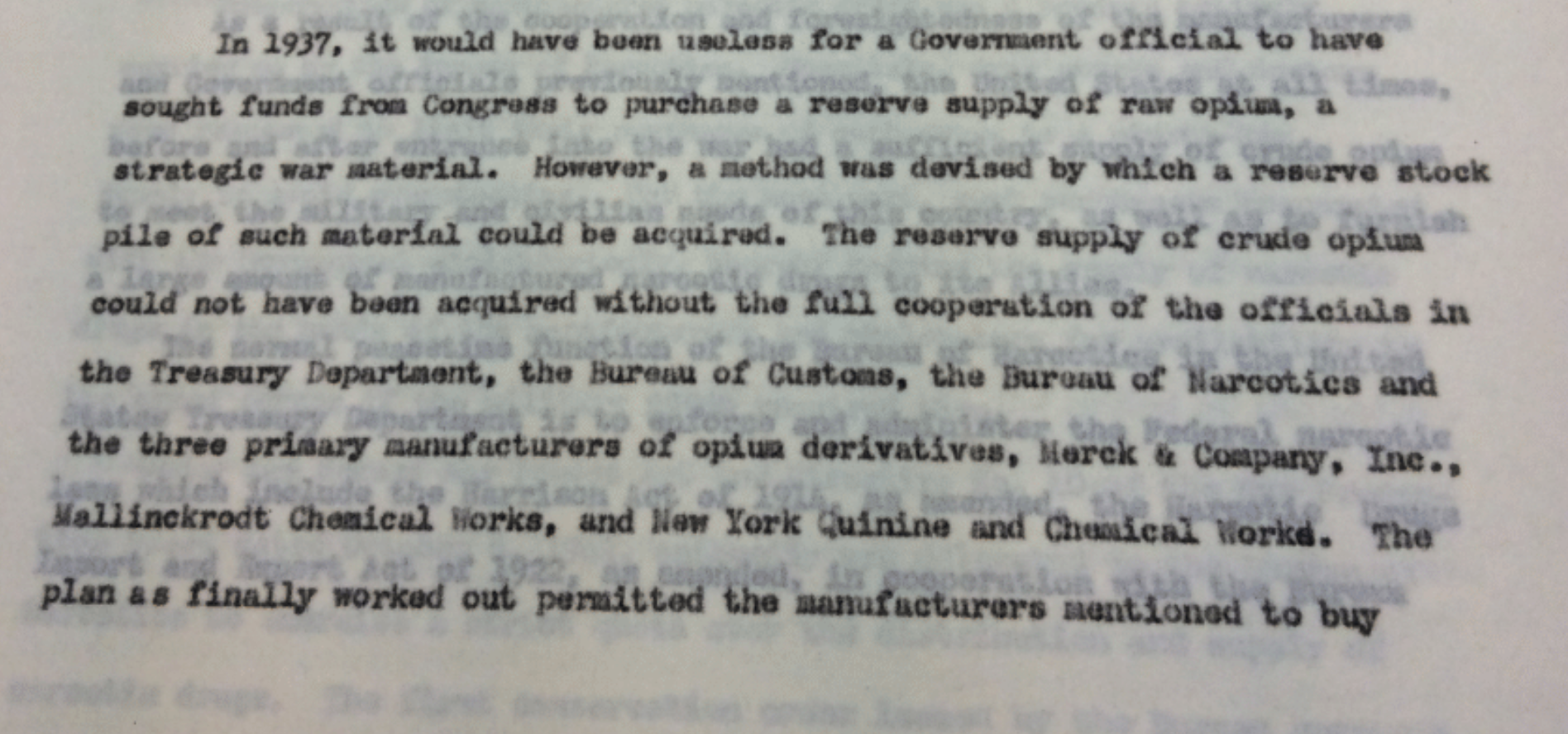

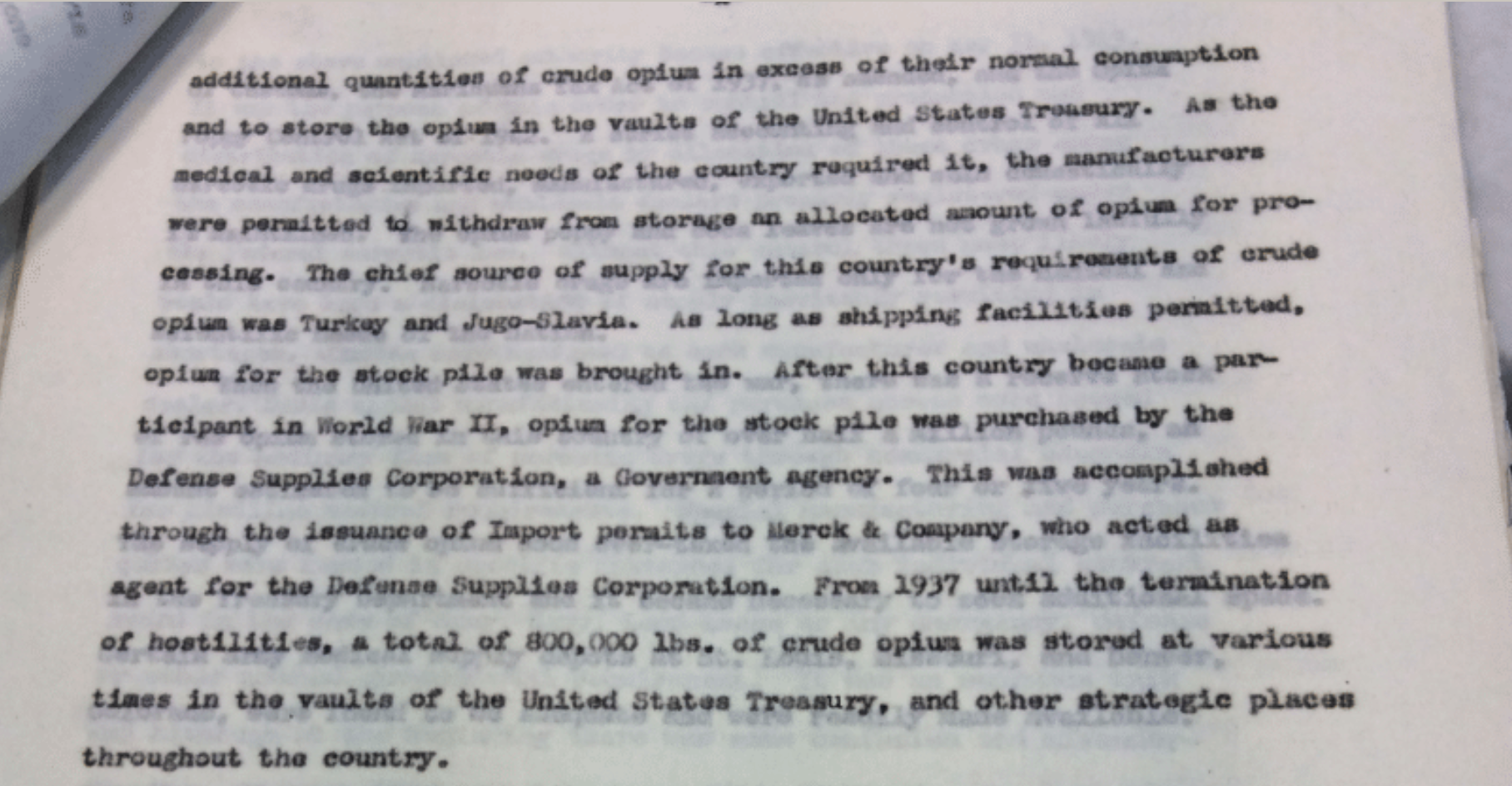

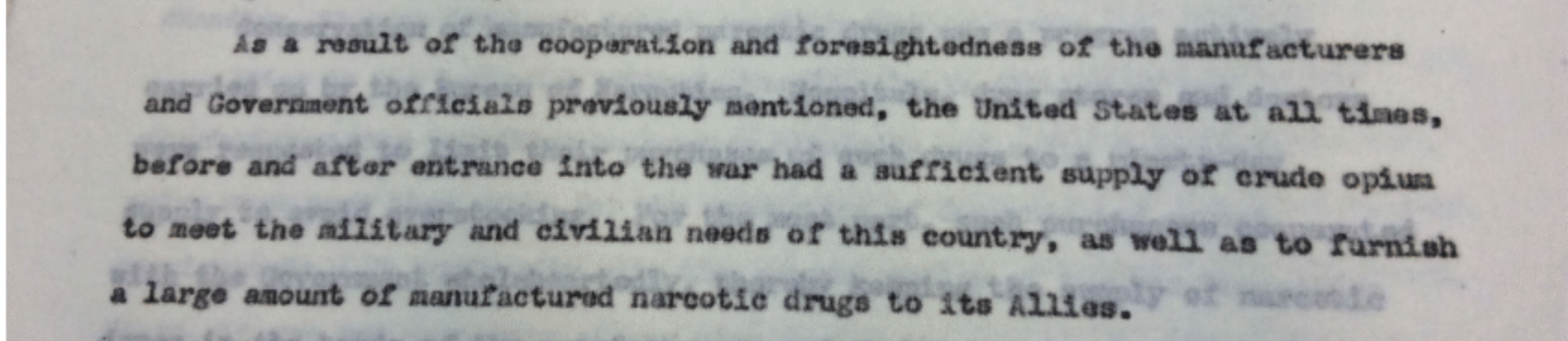

Anslinger quickly fired off a reply that such reports were “utterly fantastic and go even beyond the realms of the wildest imagination”. Though lying was very much one of Anslinger’s go-to tactics, on this occasion he was telling the truth. We have copious evidence of the slow, organic, build-up of opium growing and morphine production in the late 1930s and early 1940s. It was almost entirely gringo-free. Furthermore, the United States didn’t need any more morphine for the war. Anslinger had been stockpiling raw opium from Yugoslavia and Turkey since 1937. By the time war broke out in 1941, U.S. Treasury vaults contained 500,000 lbs of opium or enough to make sufficient morphine for six to seven years of war.

Harry Anslinger, head of the FBN, actually stockpiled morphine stocks before WWII. NARA, RG170, Box 49.

So should we simply see the U.S. Mexican morphine pact as a convenient fiction? Dreamt up by traffickers to exculpate their role, and swallowed by a populace recovering from another round of military incursion? To a certain extent, yes. To stick, conspiracy theories needed to offer simple explanations to the vulnerable.

But, to make their mark, they also have to contain small droplets of truth. In fact, the U.S.-Mexican morphine pact rested on four independent stories.

The first story concerns U.S. involvement in the early Sinaloa drug trade. Though Mexican and Chinese entrepreneurs formed the vast majority of 1940s traffickers, there was one American who played a major role in the drug business. He was the U.S. mafiosi, and Bugsy Siegel’s man in Mexico, Max Cossman. Cossman was based 500 miles to the south of the Golden Triangle in Guadalajara. But he spent pre-planting season in the 1940s up in the Sinaloa highlands offering peasants poppy seeds and credit under the pseudonym Francisco Mora. Once the poppies were grown, he had the gum delivered to his labs, where it was processed into morphine and then heroin. According to the FBN he then had the merchandise delivered to Los Angeles by plane. A tricky figure, for whom lying came easy, he could well have used the line that he worked for the U.S. government to persuade reluctant peasants.

Max Cossman, one of the roots of the U.S.-Mexican morphine pact story?

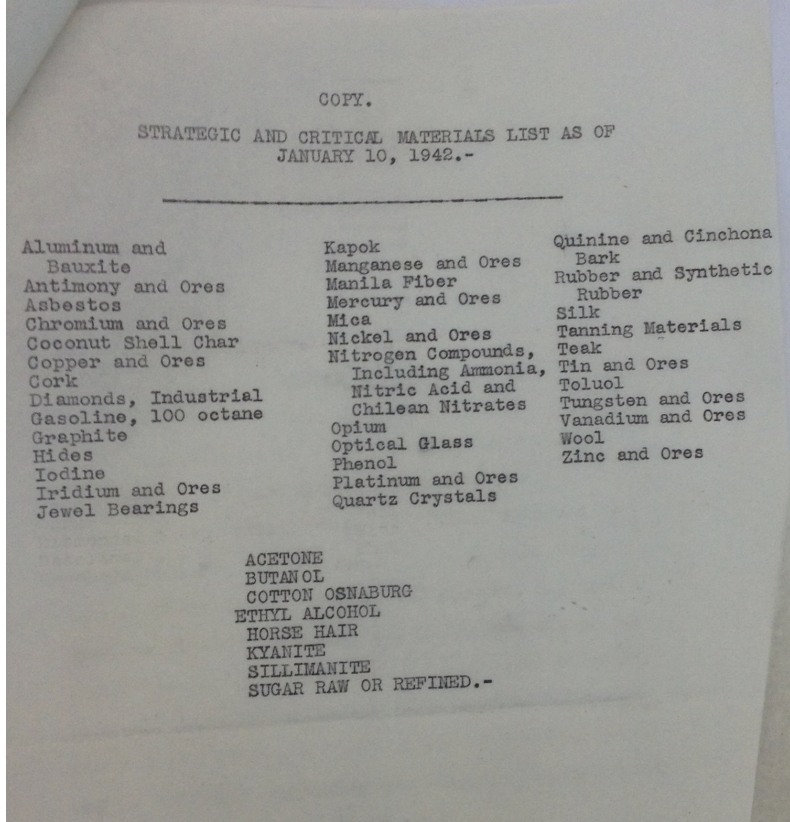

If the first story only overlapped with the U.S.-Mexican morphine pact tangentially, the others intersected with it much more directly. On 10 January 1942 Rufus Lane, the U.S. consul in Mazatlán received a letter from the U.S. Coordination Committee for Mexico. In the wake of the announcement of war, the government had set up these committees all over the globe. They were designed to search out and collect material for the war effort. The letter included a list of these “strategic and critical materials” including asbestos, graphite, manganese, nickel…. and opium. Lane now made a rather unfortunate error. He mistook the list for a general catalogue of U.S. needs. In fact, it was region specific. Opium was needed, but only in a handful of small, Pacific outposts like the tiny Indonesian island of Batan.

The list of wartime materials that probably sparked off the U.S.-Mexican morphine pact conspiracy theory

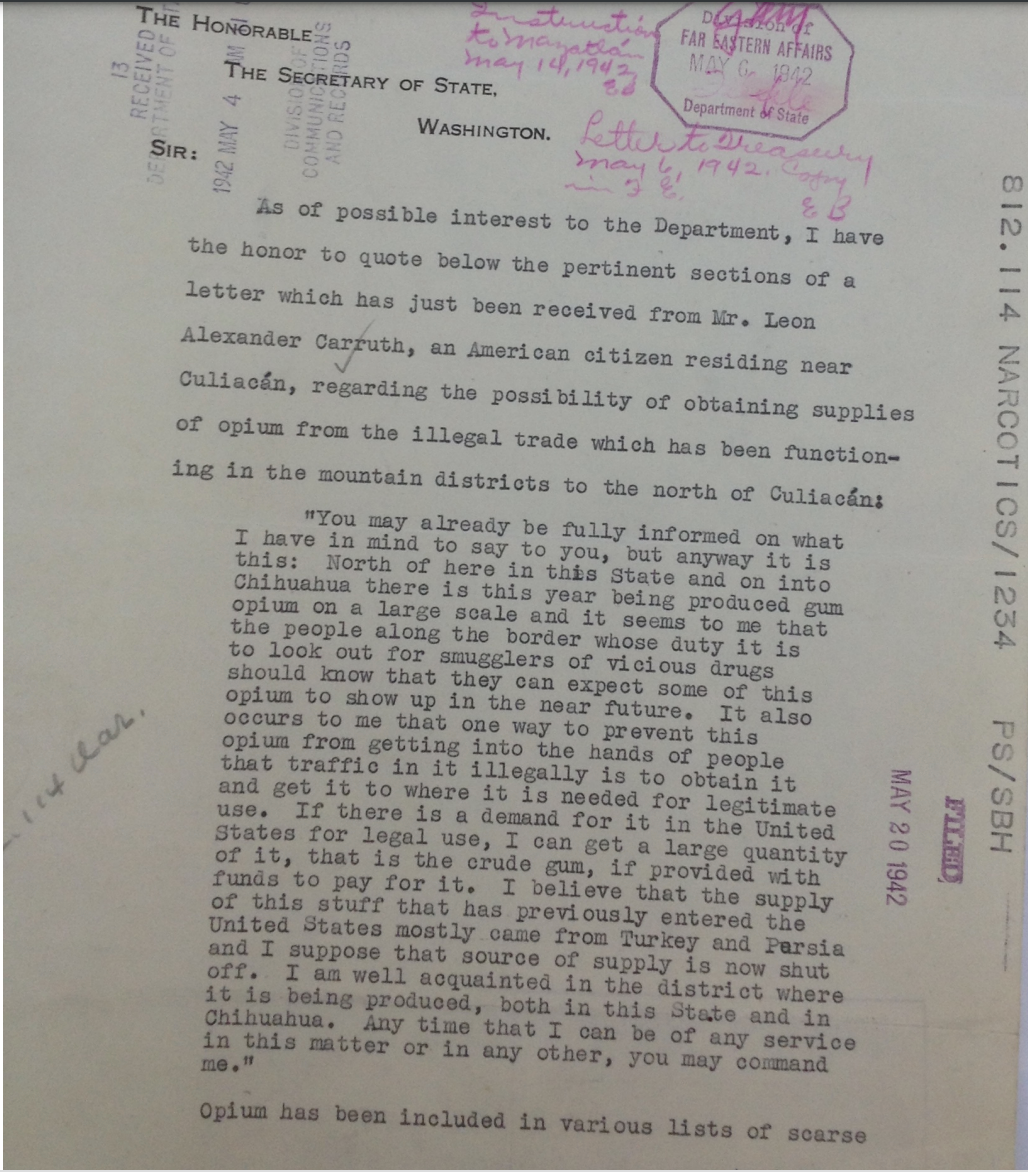

Lane now compounded this mistake by opening the request for opium to Mazatlán’s small U.S. community. The subsequent conversations were probably those that Haas, the Sinaloa play wright, overheard. One local was particularly forthcoming. Leon Alexander Carruth told Lane that “opium gum [wa]s being produced north of Culiacán and in Chihuahua”. He suggested that one of the ways to prevent it “getting into the hands of those that traffic it illegally is to obtain it and get it to where it is needed for legitimate use”. If the U.S. needed it for the war effort, Carruth would buy it up. Lane sent Carruth’s offer to the U.S. Secretary of State and waited for the grateful response.

Leon Alexander Carruth’s offer of morphine to the U.S. government. NARA, RG170, Box 23

It was not forthcoming.

Support for the idea of securing morphine supplies from Mexico was not forthcoming.

Instead, Lane received a series of angry missives from across the U.S. government. The U.S. Treasury insisted that there was actually a “large over production of opium” and stocks were “plentiful.”. The United States therefore “discourages the planting of the opium poppy within its territory or … in any country in the hemisphere”. The Customs representative in Mexico was even more shrill in his condemnation, arguing that buying up illicit opium would not only violate the law, but also end up stimulating the poppy growing industry. “U.S. Customs would seriously recommend against any such suggestion”.

A plan for the U.S. to buy up Mexican opium then did exist, however briefly. Though it was based on a misunderstanding and quickly shut down, for a few months it was pushed by the U.S. consul and discussed among U.S. expats. Enough perhaps to jumpstart a conspiracy theory?

Furthermore, two additional events compounded this initial mistake. A few months after the Mazatlán consul had proposed a U.S.-Mexican morphine deal, two U.S. Customs agents arrived in Mexico. They were working undercover, part of a secret deal between U.S. Customs and the pro-U.S. mayor of Ciudad Juárez to entrap the border queen pin, Ignacia “La Nacha” Jasso. The two U.S. Customs agents were Harold B. Westover and W.H. Crook. They claimed that they posed as two Oklahoma druggists on the hunt for scarce supplies of morphine. On 2 April 1942, Westover and Crook were introduced to La Nacha and her supplier, a Guadalajara lawyer called Alberto Torres Ibarra. At this point, La Nacha and Torres offered the two U.S. agents a tour of her opium fields and her laboratory around the western city of Guadalajara.

One of the rare images of La Nacha, allegedly taken by U.S. agents in 1942 at her opium poppy farm.

During this tour, Torres and La Nacha’s cook – a former chemist called Luis Manuel Vasquez Corona – agreed to do a side deal with the U.S. agents. They would deliver 55 ounces of morphine to the United States in return for $3200. On 18 June 1942, Torres and Vasquez arrived in San Antonio, Texas with the morphine hidden in their car engine. They were promptly arrested, tried, and sentenced to 5 years in jail. It was – to my knowledge – one of the first U.S. undercover drug stings in a foreign country.

But it was also sketchy. Though Torres and Vasquez were sentenced for 5 years, they were out of U.S. jail and back in Mexico as free men by early 1944. Furthermore, when they were arrested again for drug charges in 1948, they had an interesting story to tell. According to Torres, the two U.S. agents that had arrested them in 1942 had not claimed to be Oklahoma druggists but rather U.S. State Department officials keen to secure a source of legal morphine for the war effort. Torres and Vasquez had arrived in the United States thinking they were working for the U.S. government.

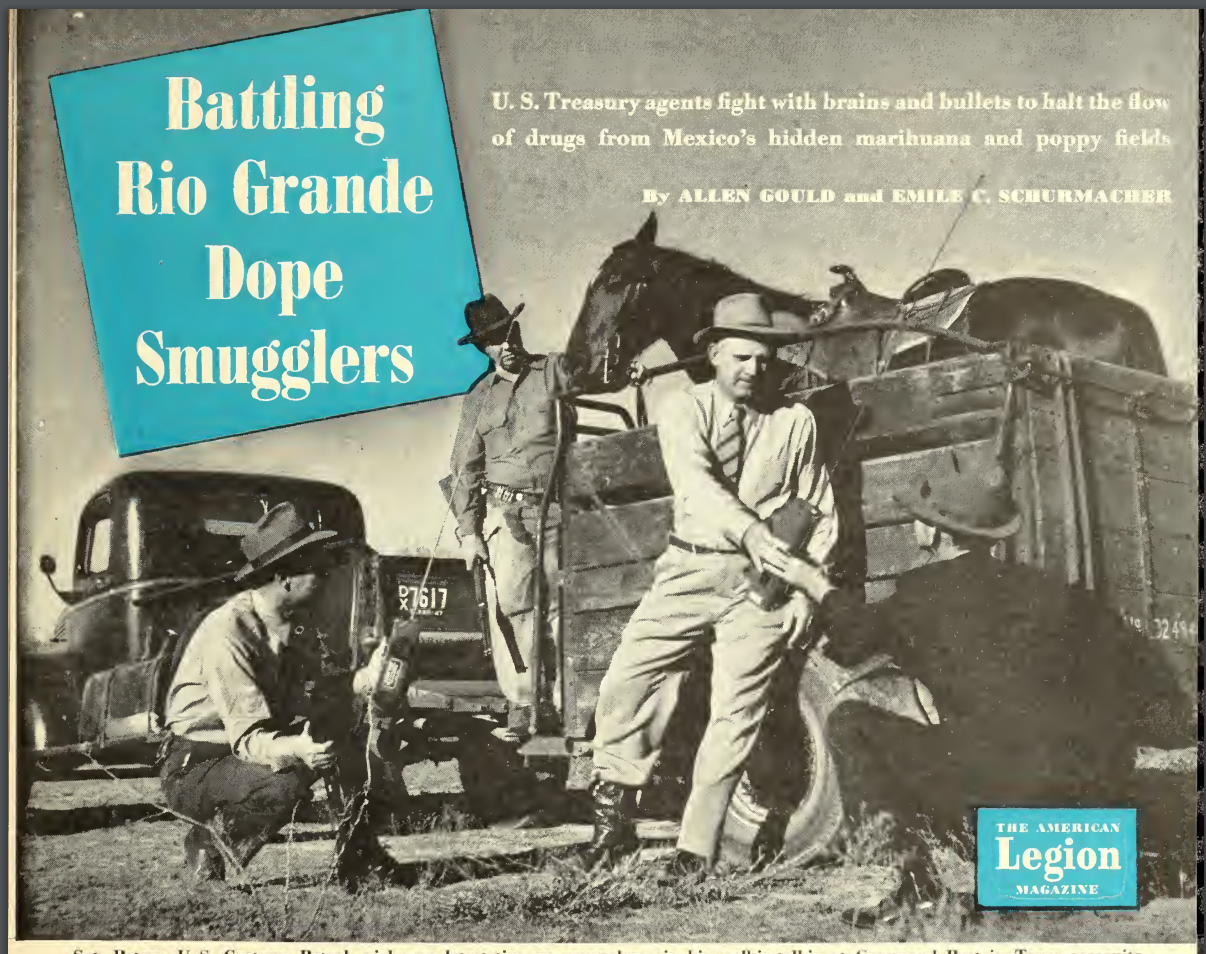

The story of the U.S. agents “fearless endeavours” in Mexico were only published six years later in 1948. Why? a) It seems that the culprits, Torres and Vasquez, got off (probably because the endeavours involved entrapment) b) The US agents failed to capture their target, La Nacha c) the United States was involved in a campaign to push Mexican authorities to send the military into opium growing zones.

It was not only entrapment (which Torres claimed was why they had been let out early). It was entrapment that would form the basis for a half century of narco-myth.

There was a final incident, which also probably played into the story of the U.S.-Mexican morphine pact. This one, for a change, involved criminals rather than incompetent U.S. agents. In 1949 or a year before the first exposé of the pact story, a certain Miguel A. Escobar sent the FBI a letter. The FBI proceeded to translate it almost comically badly. (They translated “pelo chino” or “curly hair” as “the course black hair characteristic of the Chinese”.) They then sent it to Anslinger at the FBN. Escobar claimed that an American called Mr Christe was stalking northern Sinaloa, Nayarit and Sonora pretending to work for the U.S. army as a building contractor. He used this cover to traffic both drugs and arms between the Golden Triangle and the border.

The story of the wartime U.S. chase for morphine was, in short, untrue. It was a conspiracy theory, which offered Sinaloans and other Mexicans a way to make sense of particularly vicious times. But it also contained fragments of truth, mostly connected to errors in U.S. officialdom. Woven together by the Golden Triangle’s fireside raconteurs and bar room storytellers, they morphed together into a familiar and comforting narrative of U.S. coercion and Mexican compliance.