The plan to legalize Mexican morphine

If you read The Dope, you’ll know about the radical doctor, Leopoldo Salazar Viniegra, who tried to get the laws about marijuana scrapped and implement state-run morphine dispensaries. He was a brilliant narcotics free-thinker who pre-dated the ideas of counter-culture drug radicals like Timothy Leary by over two decades. And over the past few years he has become a bit of an icon of Mexico’s growing pro-legalization crowd. There is even a rather wonderful webpage in his honor.

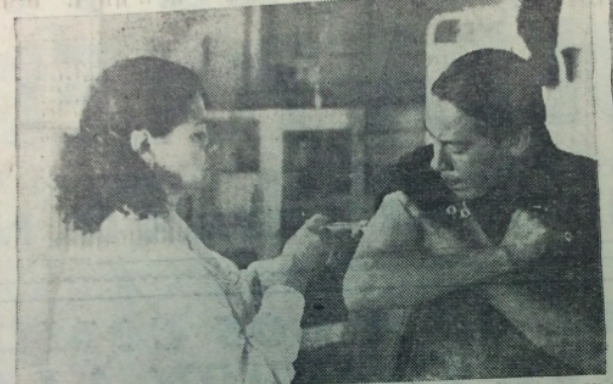

One of Dr. Salazar Viniegra’s drug dispensaries

What you probably don’t know about is the other post-revolutionary thinker who attempted to push an equally radical plan - to legalize the growing of opium poppies and the production of medical opiates.

The man in question was Triunfo Bezanilla Testa. Though Bezanilla came from Spain, he studied pharmacy at Mexico City’s School of Medicine at the turn of the century. And by the time of the Revolution he was running his father’s laboratory in the upscale Avenida de los Hombres Ilustres.

Bezanilla had a rather more ambitious view of pharmacy than most of his peers. He believed that it was the job of pharmacists not simply to measure out the required medicines but also to be at the forefront of discovering, testing, and adapting the medicines themselves. Pharmacy for Bezanilla was the intersection of chemistry, biology and medicine.

By the 1910s it was also the Revolution and Bezanilla started to link this ambitious view of pharmacy with the kind of revolutionary Mexican nationalism in vogue at the time. It was not only the job of pharmacists to discover new medicines, but to do so in Mexico’s rich, biodiverse countryside amongst its plant-savvy indigenous groups. Here was pharmacy as new age indigenismo.

During the 1930s Bezanilla’s ideas became popular in government circles. And he tried to persuade Lázaro Cárdenas to establish a Pharmaceutical Office in the major state-run farms or ejidos. This office would be in charge of reviewing the state of the drinkable water, studying the diet of the ejido workers, and creating a rural pharmacy which would grow its own medicines. By doing so these pharmacies would not only put local quacks and healers out of business, they would also undercut the big pharmaceutical companies with their inflated prices. Bezanilla’s pharmacies would bring modern medicine to rural Mexico at a fraction of the cost.

Bezanilla’s dreams for a network of Pharmaceutical Offices covering Mexico’s communal farms came to nothing. But a decade later, he saw another opportunity to push his ideas of a nationalized pharmaceutical business linked to the Mexican countryside.

The timing looked promising. The Second World War had ended and the prices of manufactured goods, including medicines, were on the rise. The President, Miguel Alemán Valdés, was looking for ideas for undercutting these expensive imported manufactured goods. So he held a series of round tables with factory owners, entrepreneurs, merchants, professionals, doctors, chemists and pharmacists.

It was at one of these roundtables in 1946 that Bezanilla first put forward an expanded version of the Pharmaceutical Office idea. He suggested that Mexico could avoid paying foreign drug companies’ prices by establishing a series of massive farm-laboratories. Here pharmacists would grow medicinal plants and transform them into workable medicines. The entire operation would be nationalized; the labs would be owned and run by the state.

Over the next four years Bezanilla expanded on his idea. And he put the production of opium poppies at the center. Again it was a matter of timing. During the 1940s farmers throughout the states of Sinaloa, Sonora, Chihuahua and Durango had started to produce acres of opium poppies. They had learned to harvest the gum; and a handful of chemists had learned how to turn this gum into morphine and heroin for the U.S. market.

But in 1947 the U.S. drug tsar, Harry Anslinger, had started to push Mexico to clamp down on its illegal drug business. The diplomatic pressure culminated in a huge, military campaign in northwest Mexico, which pulled up hundreds of acres of poppies and arrested thousands of peasants.

Rather than do the American bidding, Bezanilla had another suggestion. Rather than eradicating the crops and persecuting the farmers, the Mexican government should start a nationalize opiate industry. This would legalize an illicit industry, reduce the need for military intervention, and remove Mexico’s reliance on imported pain relief. In 1949, Bezanilla wrote,

“It is demonstrated that in the states of Sinaloa and Sonora you can cultivate the opium poppy in abundance. Yet now they are grown clandestinely, at least as clandestinely as any plant grown in such abundance can be. We have needed foreign pressure to start a battle against these transgressors of the law because of the pact that Mexico has over drug prohibition. And as a consequence of this pact, we have not only persecuted these transgressors, but also destroyed fields of opium poppies which in fact are a huge source of wealth.”

Instead, he said, the state should legalize and control the industry and use the opium gum to produce opium extract, morphine, codeine and other pain relief medicines.

For over half a century Benzanilla’s ideas have remained footnotes in works on the history of Mexican pharmacy and medicinal plants. I myself found his story in Paul Hersch Martínez’s encyclopedic Plantas medicinales: Relato de una posibilidad confiscada. But it appears that now these ideas - like those of Salazar Viniegra - may be resuscitated.

Over the past three years, a handful of local and national politicians, commentators and academics have put forward a similar proposal to both remove the influence of organized crime from rural drug growing zones and increase the amount of painkillers available to Mexican doctors. Bezanilla’s dream of a legal, nationalized, Mexican morphine industry has never been so close.