Mexican Gun Culture: Some Thoughts

Reading Ioan Grillo’s excellent Blood Gun Money and his tales of American gun culture, I started to ponder Mexico’s own relationship to guns. In the United States, there are tons of books about America’s strange obsession with the the freedom-giving possibilities of a loaded pistol. They detail the history of this obsession from the early days of the revolutionary militias to the gun fairs and Walmart weapons racks of today.

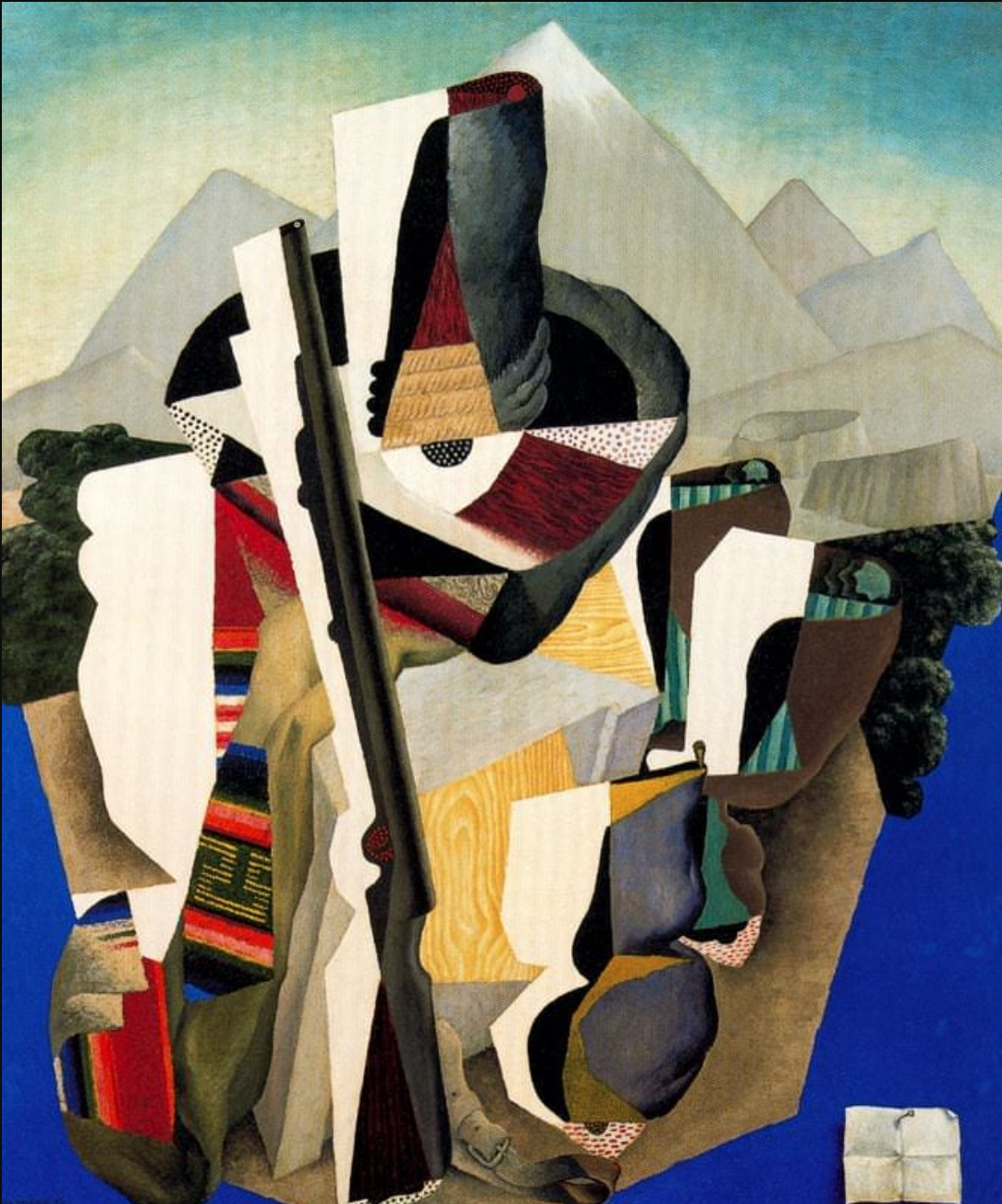

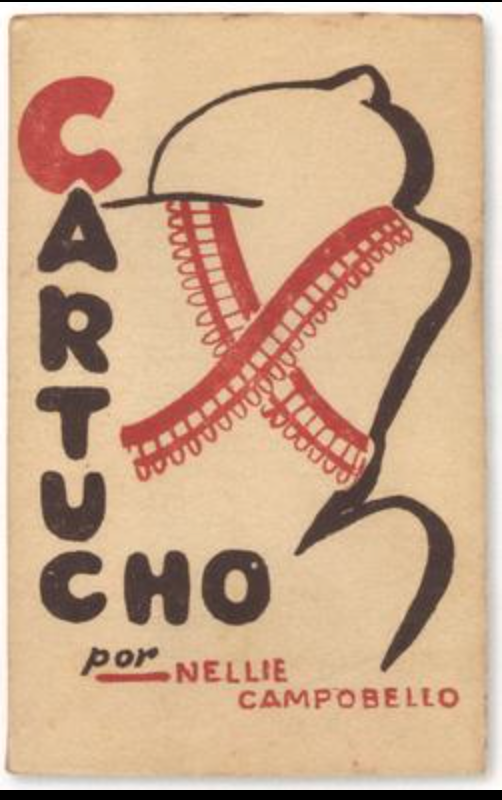

Yet Mexico has its own strong attachment to rifles and pistols which goes back at least a century. South of the border, gunplay and marksmanship makes a man and has done since at least the Mexican Revolution. It is the reason why the iconic photographs of Pancho Villa show him with bullet straps and a pair of Colt Bisleys. It is the reason Diego Rivera’s Paisaje Zapatista shows a rifle slapped between the piecemeal iconography of the Mexican countryside. And it is the reason books like Nellie Campobello’s Cartucho [Cartridge] place the gun at the center the Revolution’s vision of masculinity.

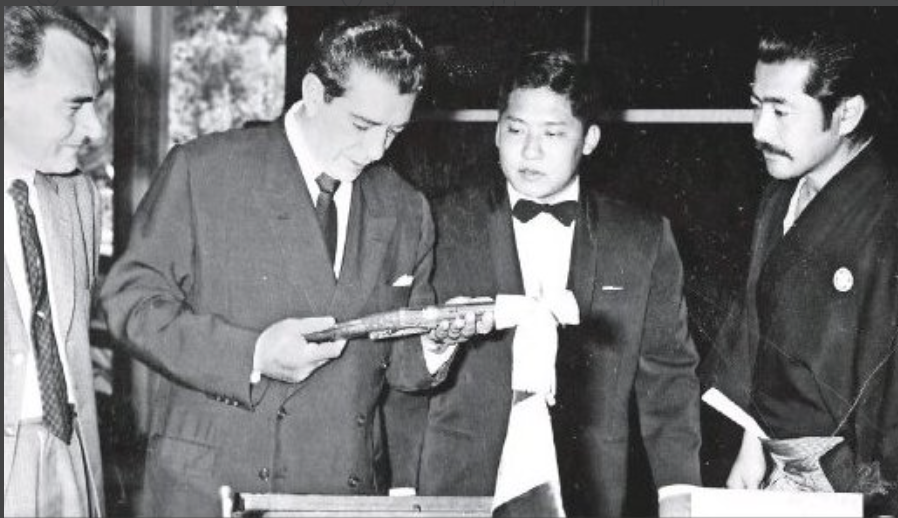

The armed phase of the Revolution ended in 1920. (Fittingly both Villa and Zapata were shot by guns. The blood-spattered Dodge Roadster that Villa was travelling in holds pride of place to the museum built in his honor). But Mexico’s obsession with guns never really went away. It was the reason most politicians would arrive in Congress armed during the 1930s. It is the reason for the proliferation of Mexican hunting and shooting clubs during the 1940s and 1950s. It is the reason, as Pablo Piccato demonstrates, why pistoleros became such an integral part of mid-century political culture. And it is the reason that every civilian Mexican president from Miguel Alemán onwards has posed for photographers holding a gun. (In fact Miguel Alemán Valdés’s museum even has a “Sala de Arma” despite the fact that Alemán was Mexico’s first civilian president).

As with everything in Mexico, there were, no doubt, regional variations. And gun culture seems to have been particularly prevalent in Sinaloa. During the 1910s highland revolutionaries competed with their skills with a Winchester rifle. There were members of the famed Carabineros de Santiago who claimed to have shot two rabbits with a single shot. The following decade, local elites turned to hunting and shooting as a leisure activity. (In fact, it was on one of these hunting expeditions in 1923 that the resident Culiacán health official discovered one of the state’s first big poppy plantations).

And by the late 1930s conflicts over land had pushed sharp-shooting pistoleros to the fore. They were employed by both peasants and landowners to take out rivals. Adverts in local newspapers reveal that merchants like Robert Mejia, Aurelio Estevez and the Cia Mercantile Engum did a brisk trade in guns and ammunition. Such was the local attachment to guns that deaths by firearms in Sinaloa – as a percentage of overall homicides – reached over 60 per cent (or similar to the present day). And, one of the first books on the subject of pistolerismo by roving journalist Mario Gil was focused on the state.

In fact the first ever narco-novel, Angelo Nacaveva’s Diario de un Narcotraficante, gives a pretty good indication of how this localized gun culture shaped the life of early narcotraficantes. Set in the 1950s the book tells the story of a group of Culicán friends and acquaintances who get involved in the drug trafficking business. When Nacaveva and the gang are not drinking they are wandering into the hills outside Culiacán to practice their shooting. They shoot cans and bottles and compete with one another over accuracy. Guns are leisure equipment first and tools of the trade second.

Copies of the first edition of Diario de un Narcotraficante now go for £3000.00

What all this suggests is that the current narcoculture obsession for flash pistols and heavy automatic guns is not simply a function of (U.S.) supply and (Mexican) demand, It is also linked to a culture in which masculinity and power are linked to expertise with a gun. America’s thriving gun market fell on fertile ground south of the border as well.